[Rink Rap note: Although the following article below gets an updated headline contextual to the Oct. 12 naming of the Boston Bruins’ All-Centennial Team (of 20 players: 12 forwards, 6 defensemen and 2 goaltenders), I wrote this a few (five?) years back for the Sports Museum’s Tradition event program. An edited version can be found in an actual copy, but this is what a search dredged up in my computer. I have long felt that Wayne Cashman’s reluctant captaincy is the most-underappreciated chapter in modern Bruins history. While the late ’70s Lunch Pail team might be the most-beloved Bruins team ever, Cashman has often been glossed over as a remnant from the Big, Bad glory days. So I was most thrilled on Sept. 7 when the All-Centennial Committee so convincingly recognized him as a top-20 Bruin of all-time. Wayne didn’t make the trip to Boston for last week’s festivities, but it was great to see him and his presenter Phil Esposito for the Tradition.]

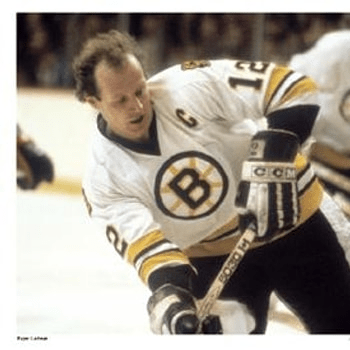

If the “B” on the Bruins’ crest were black and blue and its spokes red, then Wayne Cashman would have been the face of the franchise and his No. 12 would be hanging tonight from TD Garden’s rafters. But the winger skated in the shadows of Bobby Orr, John Bucyk and Phil Esposito, and even led from the rear when Terry O’Reilly and Ray Bourque found NHL stardom.

Only once was Cashman a star – in 1974 when career highs in goals (30) and assists (50) landed him in his only All-Star Game and, at season’s end, on the NHL’s Second All-Star Team. But all his seasons had one thing in common: Whether digging out assists for Esposito over his first seven seasons as a NHL regular or wearing the “C” over his final seven, Cashman played every game like it was his last.

“I started with Wayne my first year in Oshawa … did I think he was going to be a player? Absolutely. Did he play an important role in our success? Absolutely. If you needed him to do something for your team, he could play anywhere you wanted,” said Orr.

“Cash” had eight 20-goal seasons while playing his entire, 17-year NHL career with the Bruins, but his right-handed stick blade bent more like a garden tool than a goal tool and he made an art form of digging pucks out of Boston Garden’s quirky corners.

To no surprise, his 516 career assists dwarfed his 277 goals, but what may surprise some is his 793 points rank sixth all-time in club history. Cashman also had 31-57-88 totals in 145 playoff games, twice winning the Stanley Cup with the Bruins and earning a spot on the Team Canada roster for the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviets (2 assists in 2 GP).

Switching to his off wing, Cashman was the cog that completed Esposito’s line with Ken Hodge. He would later skate in myriad combinations, but the only role he didn’t welcome with open arms was the one that put him in the spotlight.

The Bruins were a changing club in the mid-70s amidst the departures of Orr and Esposito, the World Hockey Association and NHL expansions. The captaincy brought a heavy load and Bucyk was sidelined with a back injury when Don Cherry came calling.

“I told Cash in New York, ‘You’re going to be captain,’ and he said, ‘No, I don’t want to be captain.’ But he’s a best captain I ever had. After he was captain, I didn’t even worry about the dressing room,” said Cherry, who coached the Bruins from 1974-79. “He always reminded me of John Wayne. Quiet in the dressing room, never said a word. But, if he said something, everybody listened.”

With Cashman leading the way, the Bruins avenged their 1974 and ’76 playoff defeats against the hated Flyers with a sweep in their ’77 Cup semifinal and a five-game ouster in ’78. Had it not been for “too many men” in Game 7 of the ’79 Cup semis at Montreal, Cashman’s two goals on Ken Dryden would have gone down among the great clutch performances in sports history.

“I remember (Boston Globe writer) Fran Rosa called us the ‘Lunch Pail Gang’ … We were probably the toughest professional sports team of all time, but what we did was outwork people,” said Cherry. “We had 11 20-goal scorers (in 1977-78) and that’s the way Cash liked it.”

Like Bucyk, Cashman was too familiar with back problems. Ever since crashing into a goal post during the 1972-73 season, he played in pain and was targeted by rivals. Most famous was the night he and big Buffalo defenseman Jim Schoenfeld crashed through the Zamboni doors at the Auditorium and fought in the runway.

“I can’t believe there’s ever been a player who had a higher pain tolerance than him,” said Harry Sinden, Cashman’s first NHL coach and last GM. “I’ve seen him lying on the training room floor 20 minutes before a game for his back. He was constantly in pain and, if we had a game, he was still going out to play. Not in all my years, have I ever seen a player who could tolerate pain like him.”

Sinden recalls the late ’70s, preseason game at the Spectrum when a Bruins-Flyers brawl spilled into the concourse that ran between the teams’ dressing rooms. The event was chronicled by late author George Plympton in his book, “Open Net.”

“(Plympton) played a little for us, but he went up and had a big press conference and he didn’t see this happen,” said Sinden. “Cash went up the stairs and (Paul) Holmgren went up, and they ran at each other up there. Both benches came up and went after each other. The Flyers’ owner, Ed Snider, ended up in the middle of it; so did I and we almost went at it. After that, they put up ‘the Cashman gate.’ Only the Flyers could make that happen.”

Cherry was often befuddled shortly before game time when his captain went missing.

“This was in the playoffs. Just before the game, he’d disappear all the time. Here I am in the stick room and the stick boy is doing up his skates. That’s how bad he was,” said Cherry. “I used to watch him when he tried to get up the plane. He burned his back with hot stuff so he wouldn’t feel the pain.”

Cashman’s 1,041 regular-season penalty minutes rank him fifth all-time on the Bruins’ list, topped by O’Reilly (2,095). With O’Reilly, Stan Jonathan, John Wensink and Al Secord, Cashman the captain didn’t need to fight as often, but he was up for any challenge.

He didn’t even wait for the puck to drop to change momentum before a Game 6 in Los Angeles, cutting the microphone cord with his skate and silencing the singer of the national anthem.

This season, the Toronto Maple Leafs retired all of their “honored” numbers, taking those sweaters out of circulation. Sinden was a fan of the Leafs’ former two-tiered practice and says that, had the Bruins done the same thing, “Cash would be one of them.”

After three years out of pro hockey, then-Rangers GM Phil Esposito recruited Cashman into coaching and the former linemates rode together off the ice for a decade in New York and Tampa. Cashman was twice a head coach, with Philadelphia in 1997-98 and in the ECHL with Pensacola (Fla.). In 2001 he returned to Boston and quietly assisted Robbie Ftorek and Mike Sullivan.

Born June 24, 1945 in Kingston, Ontario, Cashman was the last player from the “Original Six” era and a player emblematic of a bygone era of old-time hockey.

“In today’s game,” says Orr, “he wouldn’t have to be as physical, but he would be just as effective.”